ANSELM

REYLE

&

MARTIN

EDER

Buddies

by Ingeborg Harms

“Buddies” – how can such a trivial term be so appropriate?

Anselm Reyle and Martin Eder could hardly be described more accurately.

Maybe they’ve managed to maintain their friendship over many years

because of a perfect balance of similarities and differences.

“Buddies” – how can such a trivial term

be so appropriate? Anselm Reyle and Martin

Eder could hardly be described more

accurately. Maybe they’ve managed to

maintain their friendship over many years

because of a perfect balance of similarities and differences.

View from hotel room, Tokyo, Japan, 2020 © Image Anselm Reyle

The art of the two is connected by playing with the trivial and with aesthetic references to the ‘70s, ‘80s, and ’90s. At KÖNIG TOKIO, for the first time ever, both positions are shown in direct contrast in the parallel exhibitions.

Anselm Reyle: Another Day to Go Nowhere and Martin Eder: Trancelucense. A few months later, the two met for a conversation in Eder’s studio.

Martin: We’ve often pondered what it would be like if we did a show together. I think the common point of interest for both of us is the seductiveness of surfaces, the eroticism in the immediacy of the material. Formally, though, we could hardly be more different. I’m figurative whereas you do quite different subjects abstractly. Our work still fits together somehow. I don’t see any difference between a sparkling fold picture of yours and a kitten picture of mine. It’s about the sheen of the surface, the illusion.

Anselm: When I first got one of your invitations twenty years ago, there was this watercolor kitten on it. I was quite shocked. I thought, you can’t do that. But then I couldn’t stop looking at it. That doesn’t happen often, because in art, anything goes. There’s nothing that hasn’t already been done. But there was something shocking about this watercolor cat. There was a repellent element to your later works too, but also something attractive. I find that really interesting.

Martin: At that time, I was thinking, what am I going to do? I have no money, I’m a student, I have no studio, I’m going to have to manage somehow. So I started doing watercolors. I couldn’t afford a studio in those days, but you can do watercolors in the car or in the forest if you have to. So the next question was: what kind of watercolors shall I do? The answer was obvious: anything that brings life down to the lowest common denominator and might interest people. To me, that means people, animals, sex and fantastic colors. Those are the classic elements people understand all over the world.

Anselm: The response you provoked in me also happens in other people when they look at my work, I’ve noticed. It’s like, you can’t do that! You can’t sell a foil like that as an abstract painting. It’s trash of the lowest order! And yet they share my fascination with foil. It’s not that I went out of my way to make my foil paintings happen; sure, consumer goods had already been put on canvas in pop art, but not at all in abstract art. Abstract art had been spared up to that point. So when I did my first foil picture, I thought I’d done something totally out of bounds. I felt kind of ashamed, like I’d created something pornographic. I hardly dared show it to anyone.

Martin: You mean the repressed, dirty side of the picture?

Anselm: Piles of dirt are really important. Other people do them too. But it’s really about materials that can crop up anywhere, not just within our subject area, in abstract painting in my case and figurative in yours. And that’s another thing I find so interesting about your work: how long has nude painting been with us? Centuries? Millennia? Then why is it that, in this day and age, when we’re surrounded by pornography, there’s still such a taboo around it? Similarly, why can’t I take a material from the world of consumerism and use it as part of an abstract painting?

Martin Eder, The Path of Transgression (detail), 2020; oil on canvas, framed, 79 x 54 x 5 cm

© Courtesy the artist and VG Bild-Kunst

Martin: You’re right. That’s something that connects us. Lucian Freud’s nudes were not acceptable at first, and Balthus’s nudes are still censored to this day. Nudes just weren’t socially acceptable. But then at some point, they became so, for two or three decades. And now they’re not politically correct again. You can learn so much about the present by the way it deals with eroticism and sexuality, even if it’s a sober painting of a nude. It needn’t be erotic in any way. We’re heading for completely different times in the way we deal with feminism, abstraction of the body and sensuality.

Anselm: As an artist, you get drawn into the realms of the forbidden. There’s a lot of seduction, of course, but also a lot of aversion to overcome. There are these dogmas that need to be challenged, personal diktats of taste, the question of what beauty is.

Exhibition view Anselm Reyle, Trancelucense at KÖNIG TOKIO, Tokyo, 2020

© Image Ikki Ogata; Courtesy the artist and VG Bild-Kunst

Martin: Seduction is also a strong critique of the present. I mean, the capitalist system we live in is based on it. In Søren Kierkegaard’s The Seducer’s Diary, the protagonist seduces a woman only to drop her again as soon as he has got her. And she’s broken by it. In the world we live in, we’re being tempted all the time, seduced into clicking here, buying there, Amazon, fashion, whatever. We’re permanently under an obligation to consume. But the classic case of temptation goes much deeper into the sensual, into your own destruction. If you or I work with temptation, I think it’s very “of the moment.” Temptation is quite possibly our greatest enemy in modern times.

Anselm: Well said. It’s a huge subject area, and that’s why, to me, this isn’t about coming up with a new, tempting way to break a taboo every day. I see myself as a painter. That’s what I studied. A painter who works with materials from outside the world of painting—materials you’ll find in nature, but just as easily in a shop window. These materials are everywhere, and they’re my artistic language; not just the materials themselves, but also what’s associated with them. Foil, for example, is the cheapest material around but also the one with the greatest effects. But I’m very classic in the way I handle it when it comes to color, harmony, dissonance, dynamics, folds, and so on.

Martin: With me, people often think I’m reproducing found material, cat videos from the internet or whatever. But I’m not. I don’t even like cute little animals. I’m not an animal painter. I have no interest whatsoever in the creatures themselves. The kittens are just placeholders, an icon that to me signifies something spooky. We all have a repertory of symbols that just are as they are. If we started thinking about them, it would drive us crazy. But with some slightly borderline creatures, like young animals, there’s a certain ambivalence. Enlarge a kitten like that to three meters and it turns into a monster. It’s scary.

Anselm: Like the cute kitten picture, there’s an epitome of abstract painting as well. You could call what I do with my stripe pictures a cliché. I try to follow these clichés in my sculptures too, in my so-called African sculptures, for instance, which are based on souvenirs made for tourists, and which are in themselves a combination of Henry Moore and African crafts. Rather than critiquing these clichés, I try to see them as something positive, to take their color and materiality up a level, to realize them in their full glory.

Martin: It’s about creating maximum drama. That’s what emerges when I spend a lot of energy working out which iconography I’m going to get out into the open.

Anselm: You once compared painting with martial arts: you spend a lot of time taking aim before you actually strike. Where do your pictures come from?

Martin: They actually do come from dreams, from trauma. If you were a kid in the ‘70s and ‘80s, for instance, you had all sorts of consumerist rubbish programmed into your fresh young mind. It’s no different today, possibly even worse. I still have the jingles from the ads in my head now. I can’t get them out. These companies have just taken over a part of my memory. It’s like brainwashing. You’re programmed that way whether you like it or not. And in any healthy adult, all that trash will want to come out again at some point.

Anselm: Exactly. That’s another thing that our work has in common. Mine is often about these childhood traumas too. To this day, I’m still working through the taste diktats of my childhood. The ceramics I make are exactly the type of vases my mother hated so much. I always found them appealing. You mentioned “spooky.” You’re into hypnosis as well...

Exhibition view Anselm Reyle, Another Day to Go Nowhere at KÖNIG TOKIO, Tokyo, 2020

© Image Ikki Ogata; Courtesy the artist and VG Bild-Kunst

Martin: ...Because it has so much to do with finding pictures. We’re permanently under hypnosis, even at this very minute. It’s more that you have to try to get out of one hypnotic state so you can fall into the next one. Our behaviour, consumption and sexuality are all thought patterns we follow unconsciously all the time. When you’re hypnotised, you create images in your subconscious, which you then bring out. To me, that’s the same as going to my studio.

Anselm: As soon as a child opens their eyes, the first thing they see is images, which they process in some way. If someone asks me how much of myself is in my work, I say there’s as little as possible. The more space my personal gestures take up, the less space there is for the general, and for a void that might be experienced on the spiritual level. My own presence in a work is almost a distraction. And I’m not really the kind of artist who creates primarily from within anyway … But I suppose I’m selecting something, so in that sense the result has actually been through my filter.

Martin: You also have to be careful when people say something is complete rubbish or hideous. A single trainer in a bush at a motorway service station isn’t necessarily ugly. We don’t know the story of how it got there. But amongst all the crisp packets, alongside a broken dog collar or whatever, it suddenly gains a new quality of colorfulness, something novel. The rubbish doesn’t know it’s rubbish. In itself, it’s just as valuable as a diamond. A new aesthetic emerges, to be observed without judgment. And that’s the approach I take toward my memories of the restrictiveness and bigotry in the village I come from. There’s something fascinating about them. What positive things can I draw from them, without making any value judgments?

Anselm: Yes, the images are quite simply there. That’s where I would find a judgmental, critical level difficult. When it comes to interpreting a picture, I wouldn’t want to sway anybody this way or that. To this day, I still have a childlike fascination for these materials; they have a certain innocence to them. Chrome or neon lights glowing at night … Any kid can understand my art. But if you want to go at it from an art history point of view, you can do that as well.

Martin: It’s about the fact that things have a soul, a life of their own—which is the principle of shamanism. As soon as we believe The Mona Lisa is invaluable, then that’s what it becomes.

Anselm: Rothko, for instance. A Rothko can be just red, but it could be whatever, something that transports us into another dimension, provided we are open to the experience.

Martin: Art has to hurt. Once you have got the observer’s attention, you need to have something to offer. Art has to involve some form of overcoming yourself, and fear—fear of the person who created it, I mean. Otherwise people will get bored. With your works, your strength of will is visible every time. How strong you must be to believe you can do it. Initially I studied sculpture, I used to make these huge sculptures out of polystyrene, and once I graduated I actually wanted to give up art ... But then, when I realised I was going to carry on, it was obvious I had to become more professional, stricter with myself. I had to channel all my fidgeting and come up with results. It was a therapeutic approach. The more you force, limit, and pressure yourself, the more productive you are. Just having the discipline to go to the studio at eight in the morning and home again at eight in the evening.

Anselm: But that only works if you anticipate some sort of relevance in it. You and I both loved quite a bit of night life. But to then say, no, I’m going to the studio tomorrow regardless.

Martin: It’s a lot of work. People always want their rewards immediately. “Hey! Great job!” We’re living in a culture of “likes.” But most people forget how tough the journey was, the countless hours, the bits that went wrong, the toil involved in creating something where you actually feel you can say, okay, that’s really meaningful to me, and possibly for other people too. When you crumple foils, you don’t just do it in passing, it’s the result of processes that took years. It all looks so effortless, but things that look effortless are often the most difficult.

Anselm: And how did you combine your life as an artist with your nightlife?

Martin: My solution was to see art and music as two separate things. As an artist, you mustn’t adopt a persona, you have to be yourself. Art is much more honest than music. But in showbiz you can be anyone. It’s even expected if you’re an entertainer. That’s why I gave myself a different name for my role as a musician.

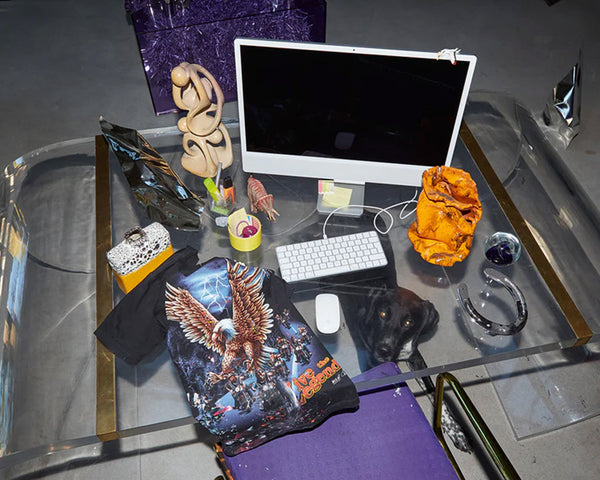

Anselm: That’s another difference between us. When I was younger, I used to express myself mainly through my appearance. I was a punk or whatever. But when the art thing started, that stopped. I suddenly started to run around looking as normal as possible. I didn’t need that other stuff any more. But for you, being a musician, the way you look in public actually matters. Something I find generally singular about you is the way you pick up on boho clichés. Nude paintings, a city-centre studio shrouded in legend with a bed right in the middle of it. You just walk in here and find yourself in a completely different world. I don’t know any other artist who celebrates that in this way. And it’s not just for show either. It’s you. And when the hypnosis thing started, it really got a bit dodgy. You never move on safe ground.

Martin: So what is it that makes reality? Our thoughts? Our memories? What we’ve learned? The ancient Egyptians were probably already asking themselves the same thing. They should teach hypnosis in schools so kids understand what makes them want a pair of Nike trainers. The purposeful manipulation we use in art is the same kind that we’re swubjected to as flirts and consumers. These are mechawnisms we should all know about. They are like objects that drop down on ropes and dangle before your eyes in the theatre. But as an artist, you’re not a victim, you’re a perpetrator.

© Interview by Ingeborg Harms, abbreviated version, original was published under the title Playmates in Vogue Germany, June 2019, pp. 170-179