JEPPE

HEIN

The

Inhospitality

of

Our

Cities

by Anne Waak

Modified Social Benches NY, 2015 © Image James Ewing

Like many things of lasting value (men’s suits, telephony) the public bench is an invention of the bourgeois nineteenth century. Taking English landscape parks as their model, liberal members of society like gardener Peter Joseph Lenné created the first public gardens and parks in Germany to offer all townspeople aesthetic pleasure and grant them respite from the rapidly advancing Industrial Revolution. While English landscape gardens were intended only for educated, liberal society, their predecessors, the baroque gardens of French palaces, were reserved exclusively for the absolute ruler and his court. Today, benches in urban parks offer strollers rest and calm regardless of their origins or social status, a place to sit and watch the world parading by or to meet up with others, often strangers.

Modified Social Benches NY, 2015 © Image James Ewing

The benches in our parks and beside our pathways are mainly used—though far from exclusively—by three groups of people: pensioners, teenagers, and the homeless. What these groups share in common is that they have more free time than most, and their lack of purchasing power excludes them from many other places and establishments such as shops, bars, and cafés. Whereas in rural areas teenagers often hang out at gas stations and bus stops (the luxury version of the park bench with a roof!), in urban contexts they tend to do so on and around the park bench. There are two advantages to this: here one can smoke in peace and demonstrate one’s disdain for the adult world by sitting on the armrest, placing one’s feet up on the seat, and occasionally spitting onto the ground. And while youth fashions are always changing, the preference for benches seems to be a kind of anthropological constant.

Modified Social Benches NY, 2015 © Image James Ewing

It is a bit cruel, then, when architect David Chipperfield claims street furniture should not offer too much comfort. More often than not newly installed benches, in train stations for example, are installed with multiple armrests along their length and with seats that slope forwards, both making them impossible to lie down on—and that’s not if they haven’t been removed entirely. A few years ago in the Frankfurt am Main neighborhood of Frankfurter Berg, a dozen benches were taken away after local residents complained about the noise made by teenagers congregating around them in the evenings. The fact that everyone else should also be deprived of these places of relaxation and encounter (people just out for a stroll, parents with their children, gathering pensioners) had clearly been forgotten. The absence of the benches was keenly felt, and they have since been reinstalled.

In his influential book Die Unwirtlichkeit der Städte (The inhospitality of our cities, 1965) the psychoanalyst Alexander Mitscherlich noted that the disappearance of urban benches is not without negative impact on well-being: “Our rebuilt cities—not when one is functioning within them between office, self-service store, hairdresser, and apartment but if one observes them as if strolling around some foreign place, seeing them for the first time—are they not depressing?” And he continues: “In these cities devoid of tree-lined boulevards, with no benches from which to observe the fascinating kaleidoscope of urban life, is it possible to enjoy oneself, to feel at home?”*

Not only park benches are disappearing. In cities, in general, there are less and less places where one can take a break without becoming suspicious. Just take one example: the new central station in Berlin opened in 2006 without sheltered or heated waiting rooms. In this glass “cathedral of transport” as it was called at the time—rather than a “cathedral of travelers”—the available space was filled not with seating but with snack bars and shops. As a result, throughout the long Berlin winter, people have to stand around in a kind of open mall with fourteen platforms and fifty-six escalators in the icy grip of an easterly wind that is rightly called the “Russian whip.” When asked to comment, Deutsche Bahn, the German railway company states that the risk of “misuse” and the cost of keeping waiting rooms open around the clock are simply too high. So, in best neoliberal style, these costs are transferred to travelers by forcing them to consume: as you can read on the Deutsche Bahn website, travelers have “adapted their needs in recent years by preferring to eat a snack or spend time in the shops while waiting for trains.” No wonder people prefer to fly. Although airports too are just gigantic shopping malls with access to departure gates; they do, however, provide seating, and with a little luck a power socket to charge one’s vital devices.

Modified Social Benches NY, 2015 © Image James Ewing

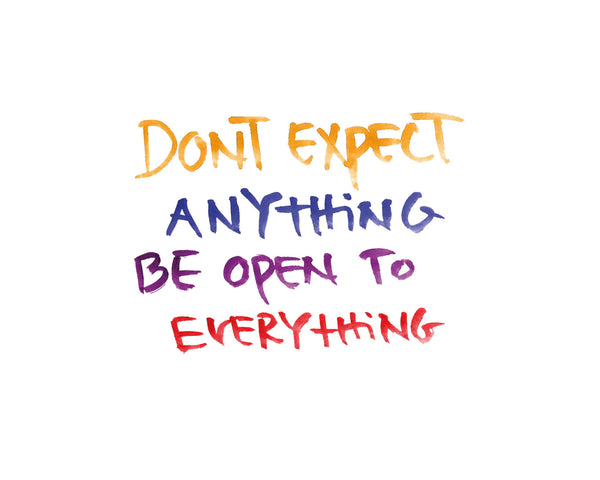

Jeppe Hein has also observed the disappearance of public benches and with them the slow extinction of places where the city is seen to be nothing more than a sphere of consumerism. Anything like social interaction is no longer part of the plan. Since 2005, the artist has been placing his Modified Social Benches in different cities around the world, some of which bear only the slightest resemblance to the kind of street furniture we are familiar with. Some have seats that sag so far in the middle that they touch the ground, others appear to have been cut in half. Some have a tree growing in their middle, others look like playground slides. Some have short stumpy legs, others have legs so long that the bench seat can only be reached by climbing. Hein’s benches are thus neither purely functional objects nor mere decoration. But they are also not public art in the conventional sense, i.e., intended only to be looked at. On the contrary, they challenge people to take possession of them. You’re supposed to let them waylay you. You’re invited to use them, spend time on them, and play with them. This ideally leads to strangers getting to know one another, sharing unplanned time together.

Modified Social Benches NY, 2015 © Image James Ewing

In this way, Hein disrupts the behavioral patterns that usually ensure we keep our distance from one another in public, that keep us moving on at a swift pace. On his Modified Social Benches people can feel temporarily at home, time and again. They can be used freely according to one’s needs. On the bench everyone can be who they are. We can take a break to ask what Hein might call life’s key questions: Who am I? Why do I exist? Where am I going? From here it’s not so far to questions like: Who are you, where do you come from, and where are you going? And even if Hein doesn’t describe himself as a political artist in the strict sense, this is where the clearly political force of his work lies.

* Translation including quotations from Alexander Mitscherlich, Die Unwirtlichkeit unserer Städt (Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp, 1965) by Nicolas Grindel.